A Place of Dreams: what kind of book should, or could, it be?

I felt really excited by Norah’s diaries, immediately, even before I uncovered the ‘love triangle’ story that would become central to my book. My excitement was because I somehow knew that they would take me on an adventure, not just into my family history, and back to the village where Norah and I both grew up and eventually left, but also into that experience that has always captured me, what we might call ‘class travel’, that is, being educated out of your class of origin, essentially. And I knew it would be an intellectual adventure too. I remember feeling like the diaries made me buzz, though I didn’t know quite what the buzzing was.

As the diaries of a working-class girl – Norah was the daughter of a postman and a former domestic servant -- her little archive is pretty unique. The lives of ordinary people generally aren’t documented in diaries and certainly don’t end up in archives; and working-class girls are probably the most under-represented in modern history. We have very few sources written by them, though plenty written about them, usually representing them as a problem in some way. As historian Carol Dyhouse has titled one of her articles, ‘Was there ever a time when girls weren’t in trouble?’ (1) For example, we have endless newspaper articles, shrieking fears about the alleged lax morality of girls and young women during the war, or commentaries by social workers, probation officers, the police, the records of juvenile court proceedings and government departments. The concerns of these are usually very far from those of the girls they document. But – with some exceptions -- these are the kinds of sources that historians are commonly forced to rely upon. Even in what we call ‘history from below’ -- history that focuses on ordinary lives – the sources used to make those histories don’t come from ordinary people themselves. Most famously, of course, is the book that started history from below, Edward Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963), which explored early nineteenth-century radical activity among men in the north of England largely from the records of government spies. So part of the excitement I felt was about what I could do with Norah’s diaries, in terms of ‘history from below’. Might they allow a different kind of access to working-class women’s interior lives?

Norah’s suitcase

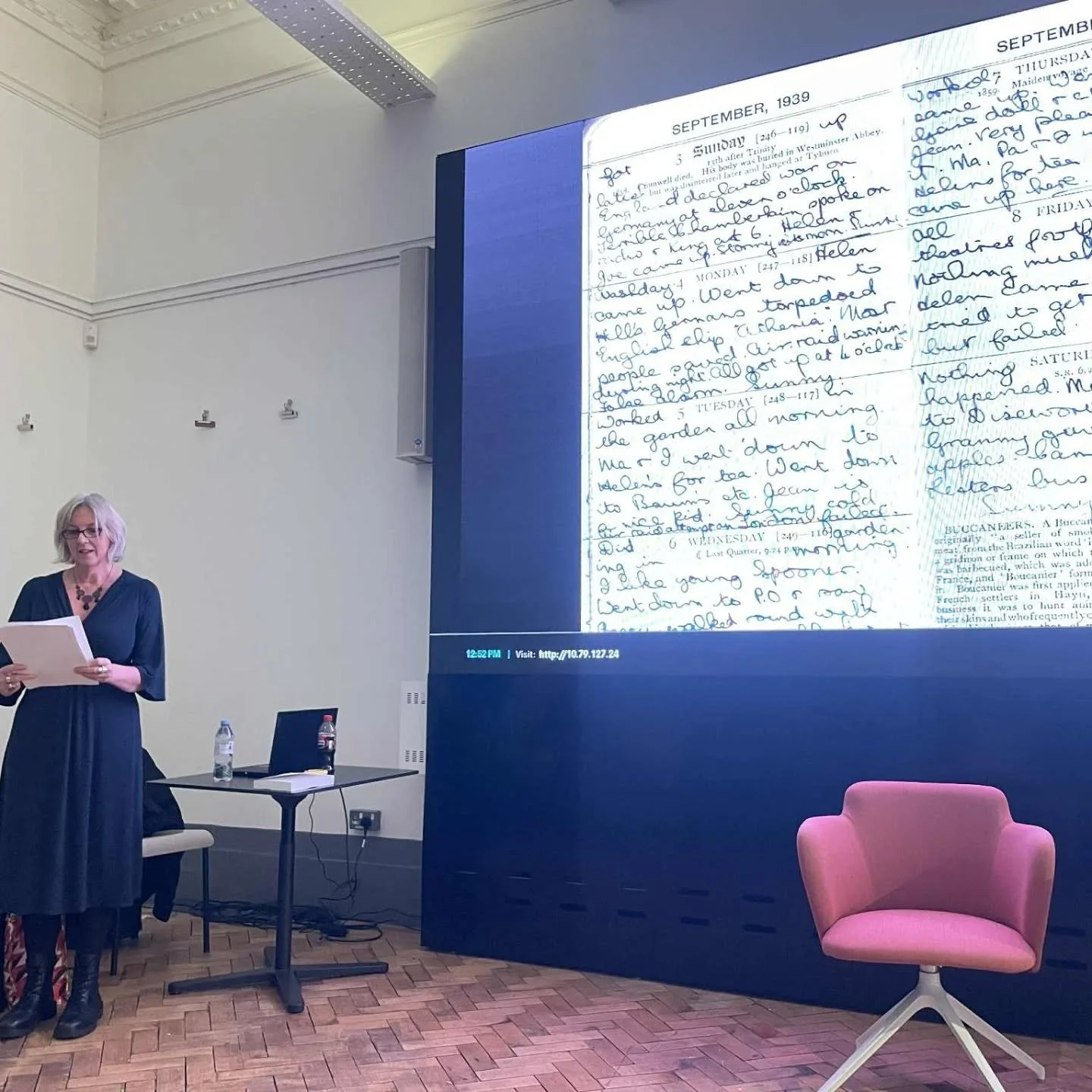

But Norah’s diaries are a challenge to read. It is not simply that much of what she wrote about was very mundane. Her daily concerns -- the weather, her routines and household chores, the comings and goings of family and friends, her health, love interests and occasional world events – were all shared with other diarists, like the middle-class women who wrote for Mass Observation during the war (2). But Norah’s diary entries – written in tiny squares that allow for no more than twenty words a day -- are more akin to almanacs and pocketbooks than the discursive, introspective diaries that find their way to publication. Her entries are laconic and telegraphic. They have little in the way of plot, dramatic tension, character development or self-reflection. Her use of parataxis, the juxtaposition of unrelated daily events, gives the ordinary and extraordinary an equal value within any given daily window. The personal pronoun, the ‘I’, is almost entirely absent. Full sentences too. Norah relies on phrases composed of verb/object pairings (‘wrote to Danny’), with an occasional adjective thrown in (‘beautiful letter from my love’). Her style is so terse as to seem almost coded, her disjointed, staccato sentences hard to decipher without insider knowledge.

Excited as I was, I didn’t feel at all confident about the diaries. Other people couldn’t see their promise. I remember my ex, my children’s father, looking at me like I was on the verge of a grave professional faux pas. ‘You’re going to make a right fool of yourself, if you try to write history from these’, he said. ‘What exactly would you write about? Who Norah sat with on the school bus in 1939? Your historian friends aren’t going to be very impressed.’ As it happens, he was right and my historian friends are generally not very impressed. But more of that later…

Behind his statement is a very a sentiment, common among historians, that the everyday life of an ordinary woman isn’t of interest. Historian Sally Alexander has recounted that when women at a History Workshop event at Ruskin College, Oxford, in 1969 declared that they planned to embark on a new brand-new venture, researching the histories of women as workers, wives and mothers, their suggestion was met by ‘a gust of masculine laughter.’ What had women ever done, except keep houses and rear children? And how did these timeless and commonplace activities warrant a history? Similarly, when Laurel Thatcher Ulrich was reading the diaries of a New England midwife who lived at the turn of the C19th, and preparing what became her Pullitzer Prize-winning book, A Midwife’s Tale, a fellow historian expressed his impatient wish that she should get back to some ‘real’ history and stop wasting her time and talents on this little women’s stuff. Ulrich was writing in the midst of the first wave of women’s history writing in the 1980s, but even a feminist scholar, committed to recovering women’s lives, had already dismissed Martha Ballard’s diaries as unimportant and uninteresting, filled with mundane entries about domestic chores and routines, insufficiently ‘epic’ to warrant attention. The eminent French scholar of girls’ diaries, Philippe Lejeune, found the same: ‘When I talk about my research’, he said, ‘I can see that people pity me.’ (3)

***

So: this weird bodily buzzing that I felt throughout my early months in the company of Norah’s diaries, was also about how I might write about them. In these early days, the one thing I felt I knew for certain was that I wanted to write a story that Norah would recognise as her own and – a separate issue perhaps -- that she might even want to read. (Whether or not I am successful with these, we can discuss later on.) Both felt very much at odds with my training as an academic historian.

The obvious way forward, especially in the context of working in a university history department, would be to write about Norah’s diaries, academic style. Academic history has much to commend it. It is trustworthy, for starters. Our skills of research mean we know our sources: their strengths and shortcomings, how they came into being, what they might mean. We are good at probing beneath the surface, steering clear of simplicity, unsettling false certainties.

But to focus first of all on my desire to write a story that Norah might recognise as her own -- I was aware that, to some extent, this meant steering clear of academic analysis, or at least, doing it differently. There have been a number of very interesting critiques particularly of oral history in recent years, where older women interviewees have protested that younger women scholars have made their stories mean something they didn’t intend in the telling, or see in them at all. This is explained in terms of operating in different frames: a second-wave feminist analysis of postwar heterosexual relationships, for example, might represent as victims women who didn’t feel victimised at all (4). When dealing with Norah’s life, I felt very aware of this tension.

This seems to me to be part of a bigger issue concerning academic history and academic writing more generally. By and large, academic historians value detachment and distance. Our points of reference are external. We open our studies with an explanation of how our research builds on what has come before; what historian Louis Masur calls ‘reciting the begats.’ We engage with this body of work in a combative manner, our findings conveyed by a ‘hidden narrator’ in a voice which is often solemn, remote, argumentative, expository. We have little truck with variety in point of view, cadence and tone. We rarely tell a story. Indeed, story is drummed out of us. (How many of the articles I have submitted for publication have had the words ‘too much narrative’ scrawled in the margin?) Despite our C20th scepticism about the possibility of scholarly objectivity, we purport neutrality. Using the ‘I’ is still frowned upon. We have no interest in – are suspicious of -- inspiring empathy, emotion and imagination. ‘Tough, tight, filled with fact and source, stripped of personal intonations,' writes Robert Nelson, academic writing is ‘scholarship served cold.’ (5)

I got very interested in coldness and warmth in writing, and in inside/outside stories. Academic history is history from the outside and it is an approach that historians are very wedded to. There have been debates since the 1960s which have questioned our commitment to this writing style and indeed which have challenged the artificial separation between literature and history. By and large, historians have ignored them. Even in what we call cross-over books, written for a non-specialist audience, the tendency is to write in a friendlier tone and with fewer footnotes; we don’t vary the voice or the form. While many historians write in very beautiful prose, it is kind of the case that the writing itself is seen as a means of packaging research, rather than something that needs looking at on its own terms.

So, moving on to my second early hope, to write a story that Norah might want to read… People outside of universities don’t read academic history books. This includes people who are passionate about history, who read historical novels, watch period films and enjoy regular visits to country houses, museums and history-themed community events. My mum is/was one such person and I had a comment from her in my mind as I started writing this book. We were in her back room and she was holding my academic monograph, published the year Norah died, stroking the painting on its cover, and then she looked at me and said: ‘It’s nice to have it on the shelf, but you wouldn’t actually want to read it.’ In the words of Hayden White, 'History continues to fascinate, but its academic variant always fails to satisfy our curiosity about the objects of study to which it draws our attention. The dead can be studied scientifically, but science cannot tell us what we desire to know about the dead.' (6)

I guess it is relevant to say that I’ve always felt a fair amount of aggro towards academic writing, and academic life generally, if truth be told. It’s hard to unpack this, but I do think it is fundamentally about social class. I’ve always felt on the edge of the profession and I have spent a lot of my career at Hallam developing community history modules, thinking about the relationship between rigorous historical research and the wider world.

So if we see academic history as writing from the outside, my desire was to get inside Norah’s diary entries, to write using her voice and from her point of view (6). And in terms of ‘history from below’, it feels to me that there is a real disjuncture between the academic style and a desire to give voice to ordinary people in the past. ‘History from below’ should be about more than a focus on ordinary people as the subjects of our research.

These are questions of voice and form. I didn’t really understand them as such at the time. I’ve always read literature, I operate at the literature end of history, if you like, but I think I’ve always read for story, and not critically, in terms of form and voice.

Anyways: enter Sheffield Hallam University MA Creative Writing…

I was out for lunch one day with the then-CL of the MA, Mary Peace, and was explaining my dilemma, no doubt at great length. And she said, well what you need is to sign up for our new Life Writing module that is coming on stream in February. I’d never thought anything about life writing. We spent the rest of the lunch unpicking terms – life writing, memoir, nonfiction, creative nonfiction, history…

The module was an utter revelation. I was so excited to do it. I absolutely loved being taken back to basics. Thinking about showing as well as telling (because what academics do, of course, is tell, until we’re blue in the face). Thinking afresh about voice and form in writing history, about what ‘history from below’ can mean, what life writing as well as family stories can bring to it…

Two readings:

(i) From chapter 3, where I introduce Norah’s first diary, her 1938 Letts’s Schoolgirls Diary. This is very much me contextualising the diary, i.e. me telling. [pp. 39, 40, 41 (leaving out top and bottom paras), 42).

(ii) The second is from the end of chapter 4 (p. 83). And the phrase ‘a poke in the eye for Hitler’ comes from Victoria Wood’s film adaptation of Nella Last’s wartime diaries, Housewife 49. This bit is imagined.

***

Okay. I’m going to dip a bit further into this stuff about history and fiction. Apologies if I’m going on too long about this – I am aware that this is quite niche, but if I can’t do it here, I can’t actually do it anywhere. Apparently, it is this interest that makes the book ‘academic’ and not ‘commercial’. And it is possible that my engagement with these issues and debates is the bit of the book that I will look back on as I enter my retirement and wonder at my unnatural preoccupation with these questions. Maybe I’ll even wish I’d done as I was told and left it out... But that isn’t where I’ve been living in the past decade, or indeed, where I am now.

Tutors on the MA were less than enamoured with my proclivity not just to tell as well as to show, but to immerse myself in the historiography and in these questions of method. This itself was a very rich tension for me. The question of whether story can carry historical interpretation, and whether I want to be reflective on that question in the book itself (bearing in mind that one of the things I am railing against is the supposed neutral, ‘hidden narrator’ of academic history writing…)

I remember particular conversations. Once, I was in a lift with Maurice Riordan, a poet, who had marked an early extract. We talked and he said ‘You need to use more of the techniques of the novelist.’ And just as I was about to counter with ‘but I’m a historian, we don’t do that’, he hopped out of the lift, glanced over his shoulder and said, ‘and I don’t mean making it up’.

What the hell? These creative writers who think they aren’t making it up? I then talked to Jane Rogers about this. I’d signed up for the Short Story module, in order to be taught by her. She’s written much that I have enjoyed, and in particular her historical novel Mr Wroe’s Virgins (1991). (I am really a C19th historian and this was right up my street…) Jane was dead matter-of-fact. She told me she did her research, and then she extracted what she called ‘a kernel of truth’ and that fed into a storyline, or enabled her to develop a character. So it turns out that these poets and novelists, these queens of making it up: they really do think they’re telling the truth, and actually, as I came to read more, including Hilary Mantel and others reflecting on their practice, they sometimes believe they are telling a deeper truth than historians can hope to reveal!

This was wild and it took me down another rabbit hole, history and fiction, for years… I found myself particularly immersed in a big debate that kicked off in Australia about Kate Grenville’s fictional representation in her 2005 novel The Secret River of ‘first contact’ between settlers and Aboriginal people in (what is now) Sydney. Grenville claimed that what she wrote was history. This infuriated historians, particularly the late Inga Clendinnen, who was absolutely adamant that it wasn’t history and that Grenville was utterly outrageous for even thinking such a thing. So with the help of Australian scholars who have explored this debate, I came to realise – to cut a very long story short -- that historians are interested in a thing that doesn’t really animate creative writers, and that is, how close we can get to real historical people and events, not just in our imaginations, but to the truth of them, and what methods we might need to use to do that. (7)

I did try to leave all this behind, but I couldn’t, and so I decided I had to kind of dramatise this conflict with creative writers. Hence it became a background thread of the book…

Reading x 3: This is from the same chapter, chapter 4, at the beginning. I have just realised that I have lost Norah’s 1940 diary (there are better examples, but they give too much of the story away). [Start at ‘By the end of the week’ (p. 66) to ‘two whole years’, ignore rest of p. 67, then read 68-9 to ‘archive’].

***

So – to the question of why it’s taken me so long to write this book... It has actually seemed at times that nobody is actually interested in these questions, except for me. Literary agents have told me as much. I’ve had a few interested, over the years, who liked the story, but were absolutely irritated to death that I should even think that people might be remotely interested in these questions of method. Also, I didn’t trust them anyway, because they kind of reel you in, and then they start to drop all manner of anti-historical bombshells. One actually said to me that ‘if you were less committed to the diaries, you could take Norah’s story in all sorts of interesting directions…’ So that idea that I needed to embellish the story in some way, be less committed to the actual sources, in order for it to be a story, started to grab me. I’m not going to disappear down this particular rabbit hole now, but the notion of what counts as a story – whose lives are interesting as life stories (not working-class lives, let me tell you), and also how we create a story out of a necessarily messy life event… I got quite lost in that. There’s a quote from Elizabeth Bowen that I love: ‘Life: the anti-novel.’ (8)

For a variety of reasons, then, the book isn’t commercial. I get that. Literary agents were not interested. In the absence of a literary agent, most publishers were unapproachable, and even those who don’t require a literary agent: zero interest.

So reluctantly, I turned to academic trade presses. But they didn’t like it either. To be fair, the woman at one trade arm did like it very much, but feared that the diaries of a working-class unknown wouldn’t sell. She wanted a more general story. Would I like to write a book about working-class women’s history more generally? Well – no. Others didn’t like the structure. I’ve deliberately written in short chapters, often with cliff hanger endings etc. One young woman said, had I not thought to write in longer chapters with more of an academic argument? I said, but I’m playing with the question of what history writing can be, what kind of writing best tells this story. This was met with a complete blank.

This mirrored responses I’ve had from historians. The best one of these comes from a colleague who was utterly affronted by my suggestion that academic writing doesn’t do what we claim it does, i.e. we are neutral, and that if we want to reach a wider audience – the ‘Impact agenda’ here – we need to think about how we write, how we might make the history we write a bit less dry and dead, a bit warmer. ‘I don’t want warmth when I am reading history’, he exploded on Zoom. ‘I want cold analysis. I have enough emotion in my domestic life. I don’t want it in the history that I read.’ It was utterly fantastic, the most emotional response I’ve had.

So it could be that I should have given up with what I wanted to do here, because if even historians don’t get it, does that mean that I am doing a lot wrong? The implication from historians – not all, but generally speaking, is that I’m being awkward, or chippy, or indulgent. It often feels quite personal, like it is directed at me, and maybe they see it that way. But I see it as part of something much bigger than a personal spat, that involves a refusal to acknowledge that these questions are valid, that they are part of valid intellectual debates and reflections on practice. It feels to me that academic historians are so confined within academic conventions that we can’t see outside of them.

I hope that by telling you all the people who haven’t liked the book, that I’m not putting you off reading it. Because of course the alternative understanding, is that this is actually a very original book. What we call ‘wider humanities’ people do seem to like it very much. And it was they who gave me the self-belief to continue with it. I had four readers who each read it more than once and gave me loads of encouragement as well as critical feedback. And then I got the reviews from OBP – from English Lit and Film Studies academics, interestingly enough -- and they were not only completely at ease with my telling this historical interpretation as a story, but they were so engaged, and so glowing about its originality and value, and really got the project… One is the endorsement on the back.

***

So: I’m drawing to a close now, but I just want to finish with something about family history. Family history has long been looked down upon by academic historians. We caricature family historians as people only interested in lists of names and dates, in small stories without context, and who get in the way when we are doing serious research in archives. As another colleague said to me: ‘You’re doing family history? Isn’t that a retirement project?’

But it isn’t possible to write ‘history from below’ without family history, because working-class people either don’t leave written materials, or if they do, they end up in a house clearance skip and not in an official archive.

So our family stories about Norah’s life and especially my mum’s memories are absolutely central to this book. I decided also to use her voice as well, as part of dramatising my engagement with Norah’s diaries.

***

My mum, Norah and Milly (my mother’s gran, Norah’s mother) at Breedon-on-the-Hill, c. 1952.

I want to end with a short reading about women and class and family history, about how family stories resonate through the generations, and how for women family history is often very different from the focus on the family tree, the male line etc. I was going to choose from a chapter where my mum and my daughters are discussing Norah’s experience, looking at what was going on in the 1940s to lead to her encounter with these men, comparing to what is going on right now – I feel very strongly about the current world in terms of young people and sex, and this is a book about raising daughters... But this would give too much away in terms of the story, and so I’ve settled on another bit about my mum and family history.

The really sad thing for me about taking so long with the book is that my mum now has advanced dementia. Since the book was published, I have hoped that I might catch her on a lucid day, when she’d remember who I am/that this is our book, that we spent years of our lives discussing, but it hasn’t happened and I think it probably won’t now.

This is from the beginning – we’ve just collected Norah’s diaries and my mum has suggested burning them. And – 10 miles/30 minutes later… [from bottom p. 12].

Notes

(1) Dyhouse, Carol, ‘Was There Ever a Time when Girls Weren’t in Trouble?’, Women’s History Review, 23:2 (2014), 272-274.

(2) Mass Observation (MO) was formed in 1937 to record everyday life in Britain. Around five hundred volunteers were recruited to keep diaries or respond to questionnaires or to anonymously record conversations and behaviour in various public places, including sports and religious events. See https://massobs.org.uk/the-archive-collections. For MO generally: James Hinton, The Mass Observers: A History, 1937-1949 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013). MO women writers include: Richard Broad and Suzie Fleming (eds), Nella Last’s War: The Second World War Diaries of ‘Housewife, 49’ (London: Profile Books, 2006); Robert Malcolmson (ed.), Love & War in London: The Mass Observation Diary of Olivia Cockett (Stroud: The History Press, 2009 [2005]); Jean Lucey Pratt, A Notable Woman: The Romantic Journals of Jean Lucey Pratt (London: Canongate, 2016); Doreen Bates, Diary of a Wartime Affair: The True Story of a Surprisingly Modern Romance (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2016); Dorothy Sheridan (ed.), Among You Taking Notes: The Wartime Diary of Naomi Mitchison (London: Gollancz, 2000 [1985]).

(3) Sally Alexander, ‘Women, Class and Sexual Differences in the 1830s and 1840s: Some Reflections on Writing Feminist History’, History Workshop Journal, 17:1 (1984), 125-149, p. 127; Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard based on her Diary, 1785–1812 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990), pp. 8-9, p. 33; ‘Patricia Cline Cohen et al., ‘Dialogue. Paradigm Shift Books: A Midwife’s Tale by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’, Journal of Women's History, 14:3 (2002), 133-161, p. 140; Philippe Lejeune, ‘The “Journal de Jeune Fille” in Nineteenth-Century France’, in Suzanne Bunkers and Cynthia A. Huff (eds), Inscribing the Daily: Critical Essays on Women's Diaries (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996), pp. 107-122, 120.

(4) See for example: Katherine Borland, ‘“That’s not what I said”: Interpretive Conflict in Oral Narrative Research’, in Sherna Berger Gluck and Daphne Patai (eds), Women’s Words: The Feminist Practice of Oral History (New York: Routledge, 1991), pp. 63-75. Katherine Borland, ‘“That's Not What I Said”: A Reprise 25 Years On’, in K Srigley, S. Zembrzycki and F. Iacovetta, (eds.) Beyond Women’s Words: Feminisms and the Practices of Oral History in the Twenty-First Century (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), pp. 31-37; Hannah Charnock, ‘Writing the History of Male Sexuality in the Wake of Operation Yewtree and #MeToo’, in Matt Houlbrook, Katie Jones and Ben Mechen (eds), Masculinities in the Twentieth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2023), pp. 288-298.

(5) Robert Nelson, ‘Toward a History of Rigour: An Examination of the Nasty Side of Scholarship’, Arts & Humanities in Higher Education, 10:4 (2011), 374-387, p. 376.

(6) Hayden White, ‘The Public Relevance of Historical Studies: A Reply to Dirk Moses’, History and Theory, 44:3 (2005), 333.

(7) See Tom Griffith, ‘The Intriguing Dance of History and Fiction’, TEXT: Special Issue 28: Fictional Histories and Historical Fictions: Writing History in the Twenty-first Century, eds Camilla Nelson and Christine de Matos, 19:28 (2015); and Christine de Matos, ‘Fictorians: Historians Who ‘Lie’ about the Past and Like It’, in the same volume.

(8) Elizabeth Bowen, Eva Trout (London: Vintage, 1999 [1968]), p. 206.