I have written and led (and am available to lead!) a history walk which explores the life of Edward Carpenter (1844-1929), an important cultural figure in late C19th and early C20th Britain, who lived in and around Sheffield from 1877 to 1922.

Edward Carpenter is most famous today for his writings on sexuality and can be seen as a pioneer of the movement for gay liberation. He was the friend, possibly lover, of the famous American poet Walt Whitman. In the years immediately following the Oscar Wilde trial (1895), he lived openly with his long-term partner, George Merrill. Siegfried Sassoon wrote to thank him for his writings on same-sex attraction, whilst E.M. Forster’s visit to Millthorpe in 1912 led him to write Maurice (written in 1913-14 but not published until 1971); the characters of Alec and Maurice were inspired by Carpenter and Merrill.

In his day, Carpenter was more famous as the author of Towards Democracy (1883) and the socialist anthem England Arise. He supported what was known as ‘the wider socialism’, which combined workers’ rights with women’s suffrage, vegetarianism, teetotalism, clothes reform, housing reform and the campaign for clean air. He was a member of the Sheffield Socialist Society and the Sheffield Clarion Ramblers and opposed vivisection, imperialism, war and capital punishment. Carpenter formed and lived in a community at Millthorpe, Derbyshire, where he market gardened, wrote poetry and political works and made sandals (including a pair each for George Bernard Shaw and Charlotte Perkins Gillman, who both visited him).

The walk initially began as a project in support of the campaign by the Friends of Edward Carpenter to raise funds to commission a statue to commemorate Carpenter’s life. The research walk gradually took on a life of its own. I have led group walks for Heritage Open Days, LGBT History Month events and for the Creative Connections series at the Millennium Galleries. (See me talking about Carpenter in the Sheffield Star: 'Walking in the footsteps of Edward Carpenter to remember Sheffield's LGBT activist', The Star, 12 September 2019: https://www.thestar.co.uk/retro/walking-footsteps-edward-carpenter-remember-sheffields-lgbt-activist-549626)

In putting together this walk, I have selected sites and stopping-off points which take us to the heart of Edward Carpenter’s Sheffield. We encounter him as a rebel who rejected Victorian bourgeois codes of masculinity and ideals of polite society, as a prophet for the new socialist movement, and as a gay man who lived openly with his male lover and sought to change public attitudes to sexuality through his writing.

See below for a timeline of Carpenter’s life in Sheffield/NE Derbys and an introduction to his historical importance.

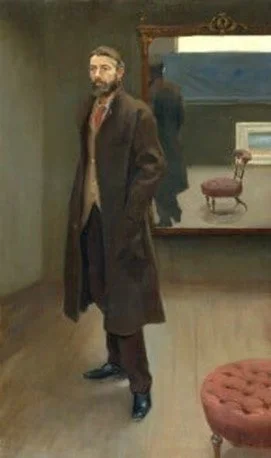

Edward Carpenter, by Roger Fry. Oil on canvas, 1894 (NPG 2447)

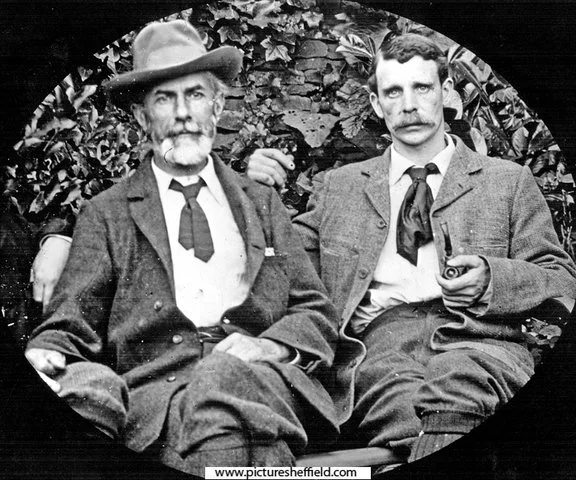

Edward Carpenter and George Merrill. Photographer Alfred Mattison. © Sheffield City Archives and Local Studies Library.

The Edward Carpenter Walk makes extensive use of the fabulous Carpenter Collection in Sheffield City Archives, as well Sheila Rowbotham’s excellent biography, Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love (Verso, 2009). Former students on the history degree at Sheffield Hallam have also made important contributions: my thanks to Kieran Harpham, Caitlin Russell and Joseph Hayes.

I have written about writing the walk: see Alison Twells, ‘Iron Dukes and Naked Races: Edward Carpenter’s Sheffield and LGBTQ Public History’, International Journal of Regional and Local History, 13: 1 (2018), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/20514530.2018.1451446

The walk is included here as a PDF (coming soon). This is preceded by a timeline of Carpenter’s life, immediately below, and an introduction to Carpenter’s life, interests and historical importance and outlines key themes: Carpenter: the class rebel, the socialist prophet and the sex reformer/lover of men.

Edward Carpenter in Sheffield:

Timeline

1844: Born in Brighton, into a naval/military family

1873: Leaves Cambridge and the church to work for the University Extension Movement in Leeds

1877: Carpenter’s first visit to America (and Walt Whitman)

1877: Arrives in Sheffield

1879: Moves to Bradway

1881: Mother and father die, leaving him a rich man. Ends his employment with the University Extension Scheme. Writes first part of Towards Democracy in Bradway garden

1883: Carpenter publishes first part of Towards Democracy; moves to Millthorpe

1884: Carpenter’s second visit to America

1886: Sheffield Socialist Society formed; Carpenter meets George Hukin

1886-1887: Commonwealth Cafe; Carpenter and Hukin break up

1887: Publication of England’s Ideal

1889: Publication of Civilisation: Its Cause and Cure

1891: Visit to India and Sri Lanka (then Ceylon)

1891: Meets George Merrill

1896: Publication of Love’s Coming of Age

1898: Merrill moves in to the Millthorpe cottage

1900: Attacks Boer Wars

1908: Publication of The Intermediate Sex

1915: Publication of The Healing of Nations

1916: Publication of his autobiography, My Days and Dreams; anti-war pamphlet Never Again! (taken from above book) is widely distributed throughout Europe

1922: Carpenter and Merrill move to Guildford, Surrey

1928: George Merrill dies. 1929: Carpenter dies.

An Outing with Edward Carpenter:

introduction

Now and then in our human society one arises who does not conform in any sense to pattern…They are men of quiet strength and purpose who seem to speak and act unmoved by the transient emotions and reactions of the crowd about them – St Francis, Tolstoy, Thoreau, Gandhi… Edward Carpenter was such a man. (GBH Ward, secretary of Sheffield Clarion Ramblers, memorial service for Edward Carpenter, 1947)

When Edward Carpenter (1844-1929) came to the north of England in 1874 to work as a lecturer for the University Extension Scheme, he was a young man with many doubts and dissatisfactions. He was frustrated by the confining gentility of his upbringing in an upper class military family in Brighton. He was doubtful that his ordination following the completion of his mathematics degree at Cambridge University had been the right decision. He also had anxieties about his future in terms of personal relationships and sexuality. Carpenter wanted a different life and his radical Christian sympathies and keenness to move beyond ‘polite society’ inspired his move north.

It was not an easy move. As Carpenter wrote on his arrival in Leeds in the mid-1870s:

I had never been in the Northern Towns. I was profoundly ignorant of commercial life. The manners, customs, ideas, ideals, the types of people, the trades, the manufactures, the dominance of Dissent, the comparative weakness of the Established Church, the absence of art, literature, and science, the dirt of the towns, the rough heartiness and hospitality – all formed a strange contrast to Cambridge and Brighton.[i]

In July 1877, after two years in Leeds, Hull and York and following a trip to America during which he met Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson, Carpenter arrived in Sheffield. The smoke-filled town centre did not suit him and his lodgings with elderly sisters in Broomhill were less than comfortable. He lectured in Sheffield, Chesterfield, York, Hull and Nottingham on a weekly basis, and was tired by all of the travelling. But he liked Sheffield and its inhabitants:

Rough in the extreme, twenty or thirty years in date behind other towns, and very uneducated, there was yet a heartiness about them, not without shrewdness, which attracted me. I felt more inclined to take root here than in any of the Northern Towns where I had been.[ii]

In 1879, Carpenter moved to a farm in Bradway on the south eastern edge of Sheffield, where he began to develop his interest in market gardening and rural community. His connection with Sheffield centre remained strong and centred on politics, leisure, sex and love.

Carpenter the class rebel

These three lines are from Carpenter’s Whitmanesque poem, Towards Democracy:

World of pygmy men and women, dressed like monkeys that go by

World of squalid wealth, of grinning, galvanized society,

World of dismal dinner parties, footmen, intellectual talk...[iii]

Carpenter experienced bourgeois life as oppressive in the extreme. He noted that men of his class were not only emotionally reticent but completely out of touch with their inner selves. They were stiff and buttoned up and lived lives based on status, materialism and a hollow respectability and bounded by ‘false shames and affectations’.[iv] He later explained that he saw the Victorian Age as:

a period in which not only commercialism in public life, but cant in religion, pure materialism in science, futility in social conventions, the worship of stocks and shares, the starving of the human heart, the denial of the human body and its needs, the huddling concealment of the body in clothes, the ‘impure hush’ on matters of sex, class-division, contempt of manual labour, and the cruel barring of women from every natural and useful expression of their lives, were carried to an extremity of folly difficult for us now to realise. [v]

In the words of E.M. Forster, in coming north, Carpenter ‘had escaped from culture by the skin of his teeth.’ [vi]

Carpenter credited the American poet Walt Whitman with enabling his 'waking up to a new day'. [vii] Whitman’s emphasis on the dignity of labour, the value of comradeship, the honesty and authenticity of the unpolished life, and the physical body and significance of individual desires, resonated deeply with him. In Forster’s words again,

With him [Carpenter] it was really a case of social maladjustment. He wasn’t happy in the class in which he was born... He didn’t revolt from a sense of duty, or to make a splash, but because he wanted to.’ [viii]

We might say: because he had to. Carpenter came north in the hope that immersion in a very different culture would save him from affectation and respectability. He wrote that in Sheffield,

Railway men, porters, clerks, signalmen, ironworkers, coach-builders, Sheffield cutlers, and others came within my ken, and from the first I got on excellently and felt fully at home with them – and I believe, in most cases, they with me. I felt I had come into, or at least in sight of, the world to which I belonged, and my natural habitat.[ix]

In this respect, Carpenter is unusual. Most middle-class people who engaged with working-class men and women at all saw it as desirable to educate and reform the poor in their own likeness. Many University Extension lecturers took this approach. Carpenter, on the other hand, felt that he might learn from working-class culture.

Carpenter the socialist prophet

In the 1890s and early years of the Twentieth Century, Carpenter became an inspiration and rallying point for men and women who were part of the new socialist movement. For radicals, the 1880s and 1890s were the most exciting of decades. Groups such as the Socialist League (1884) and the Independent Labour Party (1893), the Clarion Movement and the Fellowship of the New Life, focused not only on politics narrowly-defined – suffrage and a future economic revolution – but on individual ethical reform in the present day. They engaged in cultural pursuits such as poetry, cycling and rambling and believed that personal choices such as vegetarianism would create a new consciousness and usher in the New Life.

Socialism was like a new religion and Carpenter one of its prophets. After reading Carpenter’s England’s Ideal (1887), ILP activist Katherine St John Conway reported that she felt that ‘a great window had been flung wide open and the vision of the world had been shown me: of the earth reborn to beauty and joy.’[x] ‘A generation later, Fenner Brockway recalled that Carpenter’s epic poem Towards Democracy, ‘was our Bible.’ He continued:

We read it aloud in the summer evenings when, tired by tramping or games, we rested awhile before returning from our rambles. We read it at those moments when we wanted to retire from the excitement of out Socialist work, and in quietude seek the calm and power that alone gives sustaining strength. We no longer believed in dogmatic theology. Edward Carpenter gave us the spiritual food we still needed.[xi]

Carpenter’s home at Millthorpe, north Derbyshire, became a focus of pilgrimage in these years. Here, Carpenter grew vegetables, wrote books, made sandals and created a place where activists and thinkers would congregate to discuss and plan for the New Life.

It is worth saying, however, that despite being lauded in socialist circles, Carpenter’s own politics were possibly closer to anarchism than socialism, at least of the parliamentary variety.

Carpenter, sex reformer and lover of men

From 1898, Carpenter’s lover, George Merrill, lived with him at Millthorpe. This was the decade of the trial and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde for ‘gross indecency.’ The couple lived together for thirty years, their domestic companionship one of the most documented gay partnerships in this period.

Merrill was a man very certain of his sexuality; there was no ambiguity when he gave Carpenter the eye on a train from Sheffield to Totley in 1891, and followed him home. He was a rough diamond. He grew up on Edward Street, just round the corner from the Commonwealth Cafe, which Carpenter had funded in 1887. He worked, variously, as an attendant at a Roman baths in Sheffield, at a newspaper, as a waiter and later at Vickers’ River Don Works. Carpenter reported that Merrill was completely ‘at ease and quite himself in any society, aristocratic or vagabond’. He felt no guilt about ‘the seamy side of life’ and no awkwardness about his lack of education. Carpenter seems to have delighted in Merrill’s confidence and his remoteness from ‘respectability.’ He was amused, for example, by his lover’s lack of knowledge about Christianity. On hearing that Gethsemane was the garden where Jesus had spent his last night before his crucifixion, Merrill had irreverently asked: ‘Who with?’[xii]

In the 1890s, Carpenter wrote a series of popular pamphlets aimed at inspiring a new public discussion about matters of sexuality. A healthy attitude to love and sex were crucial for society, he argued, teaching individuals to be unselfish and anti-egoistic. Carpenter wanted sex to be seen and discussed as a normal, natural part of life, not hidden away in shame. The fourth of these pamphlets, Homogenic Love, and its Place in a Free Society (1894), dealt explicitly with love between men. Carpenter argued against the growing tendency (represented by sexologists Kraft-Ebing, Havelock Ellis and others) to view homosexuality as a psychological anomaly or even a neurosis. Desire between men, Carpenter argued, was natural and commonplace; it was

instinctive and congenital, mentally and physically, and therefore twined in the very roots of individual life and practically ineradicable ... sufficiently so to constitute this [homosexuality] a distinct variety of sexual passion.[xiii]

As well as perfectly normal and healthy, Carpenter argued, love between men contained great capacity for creativity, as evidenced in Greek and Renaissance art and literature.

But the climate was difficult. Although the death penalty for buggery had been repealed 1861, it still carried a punishment of imprisonment and the 1885 Labouchere Amendment (to the CLAA) had made all homosexual acts illegal. The fall-out from Wilde’s trial, notably in London, led Carpenter’s publishers to leave Homogenic Love out of his popular Loves Coming of Age (1896) until an expanded edition of 1906.[xiv]

Carpenter developed his ideas in The Intermediate Sex (1908). While contentious among many of his Labour movement friends, this book established Carpenter in the growing field of ‘sexology’. It was also important in affirming individual lives. Siegfried Sassoon was amongst those who wrote to thank Carpenter for illuminating an aspect of his own life:

your words have shown me all that I was blind to before, & have opened up the new life for me, after a time of great perplexity & unhappiness. Until I read the ‘Intermediate Sex’, I knew absolutely nothing of that subject, … but life was an empty thing, & what ideas I had about homosexuality were absolutely prejudiced, & I was in such a groove that I couldn’t allow myself to be what I wished to be, & the intense attraction I felt for my own sex was almost a subconscious thing, & my antipathy for women a mystery to me … I write to you as the leader & the prophet.[xv]

Carpenter’s writings also made it easier for writers like E. M. Forster, D. H. Lawrence and George Bernard Shaw to explore ideas about sexuality in their literature.

Recent historical research into men who desired other men in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries suggests that sexual relationships between men were not unusual in northern working-class communities. Historian Helen Smith has studied men who sex with other men in South Yorkshire in the late C19th and C20th, including men who were in Carpenter's circle. When she started the study, looking for gay men, she found very few, but she did find a lot of same-sex desire and practice. These are different things. Smith argues that sexual identity was not a ‘thing’ in the C19th. She says that 'working men's identities and sense of selfhood were not dependent on their sexuality; they were tied to their work and workplace community, their sense of regionality and the group of mates who shared these key areas.' Male intimacy, which may or may not have included sex, but which included physical and emotional affection and sharing of beds, made for a fluidity of sexual expression that can't be captured in C20th categories of sexual identity. These men had sex with other men. But most of these men would not have identified as gay or ‘homosexual’ or bisexual. ‘Sleeping with a man did not define the identity of the men that Carpenter had relationships with’, Smith writes; ‘it was just something that they did alongside all the other sexual and romantic elements in their life.’[xvi] Categories of identity were only just coming into being — helped into existence by the writing of men like Carpenter.

In developing this walk, I have tried to convey a sense of the world in which Carpenter and his comrades, friends and lovers lived, loved and dreamed. I also wish to convey a sense of the histories that lie just beneath the surface of the streets of our city. While Sheffield’s socialist past is relatively apparent, LGBT histories, in contrast, often remain hidden. With this walk, I invite you to go on an outing with Edward Carpenter and friends.[xvii]

Notes

[i] Edward Carpenter, My Days and Dreams (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1916), p. 77

[ii] Carpenter, My Days and Dreams, p. 92.

[iii] Edward Carpenter, Towards Democracy (Manchester: John Heywood, 1885), pp.147-148

[iv] Letter from Edward Carpenter to Walt Whitman, July 1874, cited in Chushichi Tsuzuki, Edward Carpenter 1844-1929: Prophet of Human Fellowship (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980) p. 31.

[v] Carpenter, My Days and Dreams, p. 321.

[vi] E.M. Forster, ‘Some Memories’, in Gilbert Beith, Edward Carpenter. An Appreciation (London: George Allen and Unwin,1931), p. 74

[vii] Letter from Edward Carpenter to Walt Whitman, July 1874, cited in Tsuzuki, Edward Carpenter, p. 30.

[viii] ‘Booktalk: the life and works of Edward Carpenter’, broadcast talk, 21 Sept 1944. Quoted in Sheila Rowbotham and Jeffrey Weeks, Socialism and the New Life: The Personal and Sexual Politics of Edward Carpenter and Havelock Ellis (London: Pluto, 1977), p. 36.

[ix] Carpenter, My Days and Dreams, pp. 101-102.

[x] In Stephen Yeo, ‘A New Life: The Religion of Socialism in Britain, 1883-1896’, History Workshop Journal 4 (1977), 5-56, p. 12.

[xi] Fenner Brockway, 'A Memory of Edward Carpenter', New Leader, 5 July 1929, quoted in Stanley Pierson, ‘Prophet of a Socialist Millennium’, Victorian Studies Vol 13, No 3 (Mar 1970), pp. 301-318, here p.301.

[xii] Edward Carpenter Mss, Notes on George Merrill, 5th March 1913, Carpenter Collection, p. 2, quoted in Rowbotham and Weeks, Socialism and the New Life, p. 82. See also Colm Toibin’s review of Rowbotham’s Edward Carpenter, ‘Urning’, London Review of Books 31:2 (29 January 2009), 14-16 http://www.lrb.co.uk/v31/n02/colm-toibin/urning

[xiii] Carpenter, Homogenic Love, and its Place in a Free Society (Manchester: The Labour Press Society, 1894), p.34

[xiv] ‘Wilde was arrested in April 1895, and from that moment a sheer panic prevailed over all questions of sex, and especially of course the question of the Intermediate Sex.’ Edward Carpenter, My Days and Dreams, p. 196. In a letter to Charles Oates, Carpenter wrote: ‘there seems to be a perfect panic on this subject in London and you have to take your life in your hands if you broach it. But really... I think they are all going out of their senses’. Carpenter to Charles Oates, 26 August 1895, Sheffield City Archives, MSS 351.64. Quoted by Helen Smith, ‘A Study of Working-Class Men Who Desired Other Men in the North of England 1895-1957’ (University of Sheffield: unpublished PhD thesis, 2012), p. 119.

[xv] Siegfried Sassoon to Edward Carpenter, 27 July 1911, Sheffield Archives MSS 386.179

[xvi] Smith, ‘Working-Class Men Who Desired Other Men...’ pp. 20-21, 80.

[xvii] The phrase is taken from Alison Oram’s article, 'Going on an Outing: The Historic House and Queer Public History', Rethinking History Vol.15, No. 2 (June 2011), 189–207.